If you have followed my guide to shooting S-Log2 on the A7s then you may now be wondering how to use the footage in post production.

This is not going to be a tutorial on editing or grading. Just an outline guide on how to work with S-log2, mainly with Adobe Premiere and DaVinci Resolve. These are the software packages that I use. Once upon a time I was an FCP user, but I have never been able to get on with FCP-X. So I switched to Premiere CC which now offers some of the widest and best codec support as well as an editing interface very similar to FCP. For grading I like DaVinci Resolve. It’s very powerful and simple to use, plus the Lite version is completely free. If you download Resolve it comes with a very good tutorial. Follow that tutorial and you’ll be editing and grading with Resolve in just a few hours.

The first thing to remember about S-Log2/S-gamut material is that it has a different gamma and colour space used by almost every TV and monitor in use today. So to get pictures that look right on a TV we will need to convert the S-Log2 to the standard used by normal HD TV’s which is know as Rec-709. The best way to do this is via a Look Up Table or LUT.

Don’t be afraid of LUT’s. It might be a new concept for you, but really LUT’s are easy to use and when used right they bring many benefits. Many people like myself share LUT’s online, so do a google search and you will find many different looks and styles that you can download for your project.

So what is a LUT? It’s a simple table of values that converts one set of signal levels to another. You may come across different types of LUT’s… 1D, 3D, Cube etc. At a basic level these all do the same thing, there are some differences but at this stage we don’t need to worry about those differences. For grading and post production correction, in the vast majority of cases you will want to use a 3D Cube LUT. This is the most common type of LUT. The LUT’s that you use must be designed for the gamma curve and colour space that the material was shot in and the gamma curve and colorspace you want to end up in. So, in the case of a Sony camera, be that an A7s, A7r, A6300 or whatever we want LUT’s that are designed for either S-Log2 and S-Gamut or S-Log3 and SGamut3.cine. LUT’s designed for anything other than this will still transform the footage, but the end results will be unpredictable as the tables input values will not match the correct values for S-Log2/S-Log3.

One of the nice things about LUT’s is that they are non-destructive. That is to say that if you add a LUT to a clip you are not actually changing the original clip, you are simply altering the way the clip is displayed. If you don’t like the way the clip looks you can just try a different LUT.

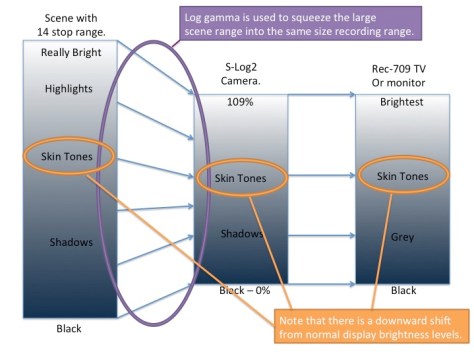

If you followed the A7s shooting guide then you will remember that S-Log2 or S-Log3 takes a very large shooting scene dynamic range (14 stops) and squeezes that down to fit in a standard video camera recording range. When this squeezed or compressed together range is then shown on a conventional REC-709 TV with a relatively small dynamic range (6 stops) the end result is a flat looking, low contrast image where the overall levels are shifted down a bit, so as well as being low contrast and flat the pictures may also look dark.

To make the pictures on our conventional 709 TV or computer moniotr have a normal contrast range, in post production we need to expand the the squeezed recorded S-Log2/S-Log3 range to the display range of REC-709. To do this we apply an S-Log2 or S-Log3 to Rec-709 LUT to the footage during the post production process. The LUT table will shift the S-log input values to the correct REC-709 output values. This can be done either with your edit software or dedicated grading software. But, we may need to do more than just add the LUT.

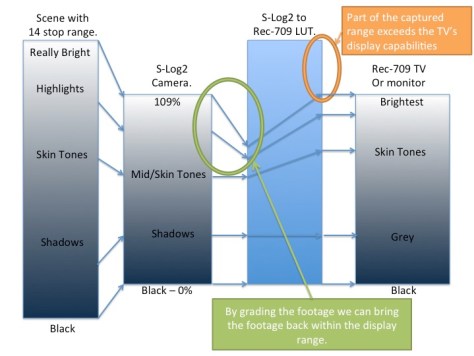

There is a problem because normal TV’s only have a limited display range, often smaller that the recorded image range. So when we expand the squeezed S-Log2/S-Log3 footage back to a normal contrast range the amount of dynamic range in the recording exceeds the dynamic range that the TV can display so the highlights and brighter parts of the picture are lost, they are no longer seen and as a result the footage may now look over exposed.

But don’t panic! The brightness information is still there in your footage, it hasn’t been lost, it just can’t be displayed. So we need to tweak and fine tune the footage to bring the brighter parts of the image back in to range. This is typivally called “grading” or color correcting the material.

Normally you want to grade the clip before it passes through the LUT as prior to the LUT the full range of the footage is always retained. The normal procedure is to add the LUT to the clip or footage as an output LUT, that is to say the LUT is on the output from the grading system. Although it’s preferable to have the LUT after any corrections, don’t worry too much about where your LUT goes. Most edit and grading software will still retain the full range of everything you have recorded, even if you can’t always see it on the TV or monitor.

If you chose to deliberately over expose the camera by a stop or two to get the best from the 8 bit recordings (see part one of the guide) then the LUT that you should use should also incorporate compensation for this over exposure. The LUT sets that I have provided for the Sony Alpha cameras includes LUTs that have compensation for +1 and +2 stops of over exposure.

IN PRACTICE.

So how do we do this in practice?

First of all you need some LUT’s. If you haven’t already downloaded my LUT’s please download one or both of my LUT sets:

20 Cube LUT’s for S-Log2 and A7 (also work with any S-Log2 camera).

Or

To start off with you can just edit your S-Log footage as you would normally. Don’t worry too much about adding a LUT at the edit stage. Once the edit is locked down you have two choices. You can either export your edit to a dedicated grading package, or, if your edit package supports LUT’s you can add the LUT’s directly in the edit application.

Applying LUT’s in the edit application.

In FCP, Premiere CS5 and CS6 you can use the free LUT Buddy Plug-In from Red Giant to apply LUT’s to your clips.

In FCP-X you can use a plugin called LUT Utility from Colorgrading Central.

In Premiere CC you use the built in Lumetri filter plugin found under the “filters”, “color correction filters” tab (not the Lumetri Looks).

In all the above cases you add the filter or plugin to the clip and then select the LUT that you wish to use. It really is very easy. Once you have applied the LUT you can then further fine tune and adjust the clip using the normal color correction tools. To apply the same LUT to multiple clips simply select a clip that already has the LUT applied and hit “copy” or “control C” and then select the other clips that you wish to apply the LUT to and then select “paste – attributes” to copy the filter settings to the other clips.

Exporting Your Project To Resolve (or another grading package).

This is my preferred method for grading as you will normally find that you have much better correction tools in a dedicated grading package. What you don’t want to do is to render out your edit project and then take that render into the grading package. What you really want to do is export an edit list or XML file that contains the details of your project. The you open that edit list or XML file in the grading package. This should then open the original source clips as an edited timeline that matches the timeline you have in your edit software so that you can work directly with the original material. Again you would just edit as normal in your edit application and then export the project or sequence as preferably an XML file or a CMX EDL. XML is preferred and has the best compatibility with other applications.

Once you have imported the project into the grading package you then want to apply your chosen LUT. If you are using the same LUT for the entire project then the LUT can be added as an “Output” LUT for the entire project. In this way the LUT acts on the output of your project as a final global LUT. Any grading that you do will then happen prior to the LUT which is the best way to do things. If you want to apply different LUT’s to different clips then you can add a LUT to individual clips. If the grading application uses nodes then the LUT should be on the last node so that any grading takes place in nodes prior to the LUT.

Once you have added your LUT’s and graded your footage you have a couple of choices. You can normally either render out a single clip that is a compilation of all the clips in the edit or you can render the graded footage out as individual clips. I normally render out individual clips with the same file names as the original source clips, just saved in a different folder. This way I can return to my edit software and swap the original clips for the rendered and graded clips in the same project. Doing this allows me to make changes to the edit or add captions and effects that may not be possible to add in the grading software.